Neovascular Phenotypes: Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

Neovascular Phenotypes: Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

Authors:

Rufino Silva, MD, PhD1,2,3; Adrian Koh, MD, FRCOphth, FRCS (Edin), MMed (Ophthalmology)2

1- Faculty of Medicine. University of Coimbra., Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Life Sciences. (FMUC-IBILI). Portugal

2- Department of Ophthalmology. Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra(CHUC). Portugal.

3- Association for Innovation and Biomedical Research on Light and Image (AIBILI). Coimbra. Portugal

4- Founding Partner & Senior Consultant, Eye & Retina Surgeons, Singapore

Updated/reviewed by the authors, July 2017.

Introduction

Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) was described for the first time in 1982(1).

Different names were proposed like posterior uveal bleeding syndrome(2) or multiple recurrent retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) detachments in black women(3).

It has a characteristic imaging expression on indocyanine green angiography (ICG), peculiar characteristics in optical coherent tomography (OCT) and apparently different responses to treatments when compared to occult or classic choroidal neovascularization.

Diagnosis is based on ICG and confirmed with characteristic fundus and OCT changes.

The primary abnormality was initially thought to involve the choriocapillaris, with the characteristic lesion consisting of a branching vascular network of vessels terminating, in one or more aneurismal dilatations, known as polyps.

Clinically a reddish orange, nodular or spheroid, polyp-like structure may be observed.

The natural course of the disease often follows a remitting-relapsing course, and clinically, it is associated with chronic, multiple, recurrent serosanguineous detachments of the RPE and neurosensory retina. In the majority of cases, there is significant long-term visual morbidity caused by fibrosis, RPE atrophy and secondary choroidal neovascularisation.

Cheung et al. reported that 50% of patients had reduction of vision to worse than 20/200 after mean follow up of 3 years(4).

A more recent knowledge has expanded the spectrum of PCV allowing us a clearer characterization of PCV. However, the classification of PCV as distinct subtype of exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) easily differentiated from other diseases and other subtypes of choroidal neovascularization associated with AMD is still controversial.

Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy has also been described in different pathological conditions including central serous chorioretinopathy(5), circumscribed choroidal hemangioma(6); melanocytoma of the optic nerve(7); pathological myopia and staphyloma(8); or choroidal osteoma(9). PCV seems to behave more like a neovasculopathy occurring in a variety of different diagnoses than a distinct abnormality of the inner choroidal vasculature(10)

Most recently, Freund and others have described PCV as part of the pachychoroid spectrum, characterised by the following clinical and OCT features: thick choroid on enhanced depth imaging (EDI-OCT), dilated choroidal vessels in Haller layer, attenuation of the choriocapillaris and inner choroid (Sattler’s layer) and loss of fundus tessellation.

While it is plausible that some patients are predisposed to development of PCV due to underlying pachychoroid, it is unclear if the mechanism responsible for inner choroidal thinning and ischemia is largely mechanical (due to compression from the enlarged choroidal vessels) or primarily driven by hypoxic and inflammatory changes in the choriocapillaris.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PCV is not completely understood. It is widely accepted to be originated at the inner choroidal level.

Polyps may develop from a choroidal vascular network or from a plaque of occult new vessels(11,14).

Yuzawa et al.(13) described the filling of PCV lesion simultaneously with the surrounding choroidal arteries suggesting that PCV lesions grow from inner choroidal vessels.

Few clinicopathological studies have been reported.

MacCumber et al.(14) examined an enucleated high myopic eye with rubeosis and vitreous haemorrhage from a diabetic patient without diabetic retinopathy, with high blood pressure and history of multiple, bilateral, recurrent neurosensory and pigment epithelium detachments (PED).

Bruch’s membrane was crossed by choroidal vessels and an extensive fibrovascular proliferation was disclosed within Bruch’s membrane and the inner retinal space. They did not observe choroidal saccular dilatations except that some choroidal veins were quite large.

Inflammation was expressed by the presence of B and T lymphocytes at the level of choroid and fibrovascular tissue and the expression of intercellular adhesion cytokines like ICAM-1 was shown.

Lafaut et al.(15) reported the histopathologic features of surgically removed submacular tissue from an elderly patient with a pattern of PCV on ICG.

A thick fibrovascular membrane located on the choroidal side of the RPE was described. The RPE layer was discontinuous whereas on its choroidal side an almost intact layer of diffuse drusen was observed.

A group of dilated thin-walled vessels were found and located directly under diffuse drusen within a sub-RPE, intra-Bruch’s fibrovascular membrane.

Dilatations appeared to be of venular rather than arteriolar origin and some lesions were associated with lymphocytic infiltration.

The presence of choroidal infiltration by inflammatory cells was also referred by Rosa et al.(16)

Okubo et al.(17) described unusually dilated venules adjacent to an arteriole with marked sclerotic changes and newly formed capillaries within the wall of the degenerate arteriole and near the dilated venule.

Therasaki et al.(18) described clusters of dilated thin-walled vessels surrounded by macrophages and fibrinous material in neovascular membranes obtained from submacular surgery for PCV.

Hyalinization of choroidal vessels and massive exudation of fibrin and blood plasma were observed in all the five specimens of PCV lesions studied by Nakashizuka et al.(19).

They also found some blood vessels located above the RPE in two of the five eyes. Immunohistochemically, CD68-positive cells were described by them around the hyalinized vessels.

There were no alpha-SMA-positive cells in the vessels of PCV. CD34 staining showed endothelial discontinuity.

Vascular endothelial cells within the PCV specimens were negative for VEGF. HIF-1alpha positive inflammatory cells were located in the stroma of specimens(19).

Hyalinization of choroidal vessels, like arteriosclerosis, seems to be characteristic of PCV(19).

All these previous histopathological studies identifying a large spectrum features (like dilated choroidal vessels, intra-Bruch’s neovascularization, inflammatory cells, drusen material, thick membranes, single saccular dilatations or clusters of dilated thin walled vessels) may partially being expressing the influence of disease stage(20).

For many authors(11,15,21-25) and following the results of clinicopathological studies, PCV may represent a subtype of exudative AMD.

Yannuzzi et al.(24,25) found a prevalence of 7.8% of PCV in a population with signs of exudative AMD and Laffaut et al.(15) described the presence of late ICG hyperfluorescent plaques in 58% of 45 cases with PCV, proposing that PCV should be considered a subtype of exudative AMD.

Many other authors(23,24,25) describe PCV cases with subretinal neovascularization.

Ahuja et al.(26) described a prevalence of PCV in 85% of a consecutive series with 16 eyes diagnosed as exudative AMD and showing a PED greater than 2 mm of diameter, haemorrhage or retinal neurosensory exudation.

According to Yannuzzi(24,25)PCV and exudative AMD may differ in mean age of onset (PCV affected patients are younger), presence of exudative peripapillary lesions (more frequent in PCV), prevalence of soft drusen (greater in AMD patients) and ethnicity (PCV more prevalent in non-white population).

PCV also has less tendency to develop fibrous proliferation and a higher incidence of PED and neurosensory detachments.

PCV and AMD share common genetic factors, which suggests that PCV and wet AMD are similar in some pathophysiologic aspects.

A common genetic background may exist between typical exudative AMD and PCV patients. Complement pathway plays a substantial role in the pathogenesis of PCV, like in AMD.

A consistent association of the ARMS2/HTRA1 locus with both neovascular AMD and PCV suggests that the two diseases at least in part share molecular mechanisms(27).

The nonsynonymous variant I62V in the complement factor H gene is strongly associated with PCV and may be a plausible candidate for a causal polymorphism leading to the development of PCV, given its potential for functional consequences on the CFH protein(28).

The LOC387715/HTRA1 variants are associated with PCV and wet AMD in the Japanese population. The associations are stronger in AMD than in PCV(29).

LOC387715 rs10490924 correlates with vitreous hemorrhage and also with the lesion size. Rs10757278 on chromosome 9p21 was shown to be significantly associated with the risk of PCV in Chinese Han patients(30).

Among the patients with AMD and PCV, those with a homozygous HTRA1 rs11200638 risk allele seem to have larger CNV lesions(31).

Another susceptibility gene in PCV, the elastin gene (ELN), has shown to be more associated with PCV than with AMD(32).

With meta-analyses, variants in four genes were found to be significantly associated with PCV: LOC387715 rs10490924 (n=9, allelic odds ratio [OR]=2.27, p<0.00001), HTRA1 rs11200638 (n=4, OR=2.72, p<0.00001), CFH rs1061170 (n=4, OR=1.72, p<0.00001), CFH rs800292 (n=5, OR=2.10, p<0.00001), and C2 rs547154 (n=3, OR=0.56, p=0.01). LOC387715 rs10490924 was the only variant showing a significant difference between PCV and wet AMD (n=5, OR=0.66, p<0.00001)33.

PCV has been referred to be associated with other ocular disorders like macroaneurysms or inflammatory diseases(11,34).

However, this association is still inconclusive and deserves further investigation.

A relation between the retinal vascular changes in hypertensive retinopathy, like vascular remodelling, aneurismal dilatations and focal vascular constrictions, and choroidal alterations in PCV was proposed by Ross et al.(34).

Epidemiology

PCV is usually diagnosed in patients between 50 and 65 years old but the age of diagnoses may range between 20 and more than 80 years.

Most patients with PCV are likely to have AMD signs.

Prevalence of PCV in patients with AMD signs ranged between 4.8% and 23% in different series and different countries(3,11-14,21,35).

It is considered to be more prevalent in Asian population(35) and African American than in Caucasian(3,11,12,21) as it seems to preferentially affect pigmented individuals.

Preference for female gender is referred in Caucasian(11,12,21) whilst in Asian population male are more affected(13,35).

Bilateral involvement is common and may be as high as 86%(21).

Natural evolution

The disease has a remitting-relapsing course and is associated with chronic, multiple recurrent serosanguineous detachment of the neurosensory retina and RPE, with long-term preservation of vision(11,24,25).

Visual acuity (VA) loss is associated with central macular involvement and may range from mild to severe VA loss or blindness.

Treatment of central macular lesions with photodynamic therapy (PDT) and more recently with antiangiogenic drugs has precluded a better knowledge of natural history of PCV with macular involvement.

Approximately half the patients with PCV lesions in the posterior pole may have a favourable course without treatment(36).

In the remaining half the disorder may persist for a long time with occasional repeated bleeding and leakage, resulting in severe macular damage and VA loss.

Eyes with a cluster of grape-like polypoidal dilations of the vessels may have a higher risk for severe visual loss(37,38).

Choroidal vascular lesions may be located in the peripapillary area, in central macula or in midperiphery.

The analysis of VA outcome must consider location of polyps and/or abnormal vascular network. Most of the PCV natural history series describe lesions in the posterior pole, differentiating macular from extramacular and/or peripapillary polyps and macular involvement ranged from 25% to 94% (12,35,38,39).

Kwok et al.(38) followed the natural history of nine eyes with macular involvement after a follow-up ranging from 5 to 60 months and found VA improvement of two lines in only one eye (11.1%), VA change of one line in one eye, and VA decrease of two lines in seven eyes (77.7%).

Uhyama et al.(36) followed 14 eyes with PCV (13 with macular involvement) for a mean period of 39.9 months and described VA improvement of two lines in five eyes (35.7%) and VA decrease of two lines in four eyes (28.5%).

A favorable course was demonstrated in 50% of the cases with the remaining half of the cases showing recurrent leakage and hemorrhages and progressive VA loss.

Lesions may grow by enlargement with proliferation and hypertrophy of the vascular component but, apparently, not by confluence.

Polyps may bleed, grow, regress or leak and a choroidal neovascularization may appear

A massive spontaneous choroidal hemorrhage is rare but may constitute a severe complication associated with blindness(37).

Progression to RPE atrophy is common and may be related with resolution of PED, chronic or recurrent leakage with PED or neurosensory detachment, autoinfarction, regression or flattening of the lesion.

Chronic atrophy and foveal cystic degeneration is associated with severe VA loss(2,11,15,23,24,25,39).

Diagnosis

The current gold standard of diagnosis of PCV is based on ICG imaging (Figure 1) and may be complemented with OCT, fluorescein angiography and fundus findings (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Clinical examination may show one or more reddish-orange, spheroid, subretinal mass located at the macular or juxtapapillary area (Figure 2).

This mass may correspond to the anteriorly projection of multiple polyps and is very suggestive of PCV.

Also very suggestive of PCV is the serous or serous-hemorrhagic PED and/or neurosensory detachment associated with extensive subretinal haemorrhages and circinate hard exudates (Figures 1,2 and 4).

Fluorescein angiography alone is not useful for PCV diagnosis.

Neurosensory detachment and serous or sero-hemorrhagic PED may suggest the diagnosis but polypoidal lesions are only visualized if the overlying pigment epithelium is atrophic.

Intermediate or late leakage on fluorescein angiography is very often diagnosed as occult choroidal neovascularization with late leakage from undetermined source or may be confused with chronic central serous chorioretinopathy.

The characteristic PCV lesion in ICG is sub-RPE network of vessels ending, in the great majority of cases, in aneurysmatic dilatations, which elevate the overlying RPE, giving rise to the characteristic sharp inverted V-shaped or thumb-like protrusions seen on the OCT.

Other important signs on OCT suggestive of underlying PCV are the irregular undulation of the RPE separated from the Bruch’s membrane (often referred to as the ‘double layer sign’) and adjacent PED.

The lesion may be juxtapapillary, macular or may be rarely located in the midperiphery.

Juxtapapillary lesions often show, in early ICG images, a radial arching pattern, and the vascular channels may be interconnected by smaller spanning branches more numerous at the edge of the lesions(39).

Interestingly, juxtapapillary lesions have been reported to be more common in patients of Caucasian and Afro-Caribbean descent compared to macular distribution of polyps being more commonly seen in East Asian patients.

When the polypoidal lesion is located in the macular area, the vascular network often arise in the macula and follows an oval distribution(39).

The area surrounding the vascular network is hypofluorescent during early phases of ICG and in late phase ICG often shows a reversal of the pattern: the area surrounding the polypoidal lesion becomes hyperfluorescent and the centre shows hypofluorescence.

In very late phases ICG shows disappearance of the fluorescence (washout) in non-leaking lesions (Figure 4-d)(11,22,24,25).

OCT and particularly 3-D OCT is very useful for diagnosis confirmation.

Documentation of polyps (number, location, size) and associated features (neurosensory detachment, serous or haemorrhagic PED, haemorrhage) may be assessed by OCT. Particular findings like the undulation of RPE (corresponding to the branch vascular network), double layer sign (the inner layer is RPE and the outer layer is the inner boundary of the Bruch/choroid complex), Bruch membrane thinning, the identification of polyps under a detached RPE and thicker choroid compared with typical neovascular AMD can be assessed as well.

Polypoidal lesion and branching vascular network identified in ICG may be visualized on spectral domain OCT in near 95% of the cases as areas of moderate reflectivity between the clearly delineated abnormal section of RPE and Bruch’s membrane(40).

Polypoidal lesions are visualized as anterior protrusions of a highly reflective RPE line.

With “en face OCT”(41)branching vascular networks were detected as elevations of the RPE.

Serous PED may be seen as round protrusions of the RPE and are often accompanied by adjacent smaller round protrusions of the RPE, consistent with polypoidal lesions.

These protrusions of the RPE are often fused and typically appeared as a ‘snowman’.

Subsequent longitudinal examination reveals the polypoidal lesions to be sharp protrusions of the RPE with moderate inner reflectivity.

Consistent with the location of the branching vascular network, a highly reflective line may be seen often just beneath the slightly elevated reflective line of RPE(40,41).

Optical coherence tomography angiography is able to detect the BVN in all cases and is located in the space between the RPE and Bruch's membrane. Polypoidal lesions can be detected in up to 85% of the cases, showing high flow signal. They are located just below the top of the pigment epithelial detachment42

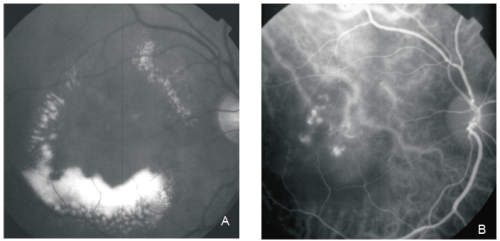

Figure 1 - PCV. Red-free (A) image with circinate lipidic exudation. Intermediate phase ICG shows an abnormal choroidal vascular network and multiple polyps in the centre of the circinate exudation (B).

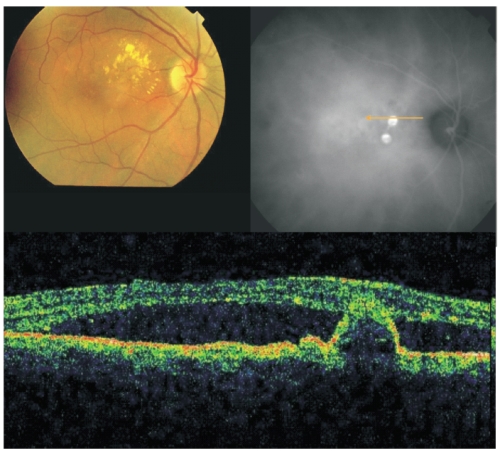

Figure 2 - Fundus colour photography with lipidic exudation and a reddish-orange, spheroid, subretinal mass located at the macular area associated with macular edema. Late ICG (top, right) reveals the presence of two polypoidal lesions in the papilomacular bundle. On OCT (bottom) the polyp is well delineated and a sub-foveal neurosensory detachment is observed.

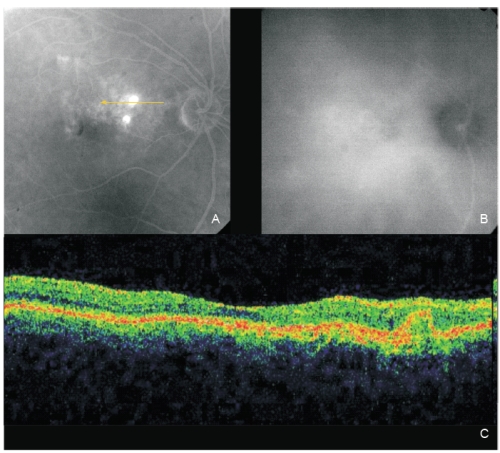

Figure 3 - Same eye of Figure 2 after one PDT session. The two polyps show fluorescein staining (A; fluorescein angiography late phase). A complete polyps resolution is observed on late ICG (B). OCT (C): An intermediate reflectivity is now registered inside the polyp limits (no fluid) associated with a complete resolution of the neurosensory detachment.

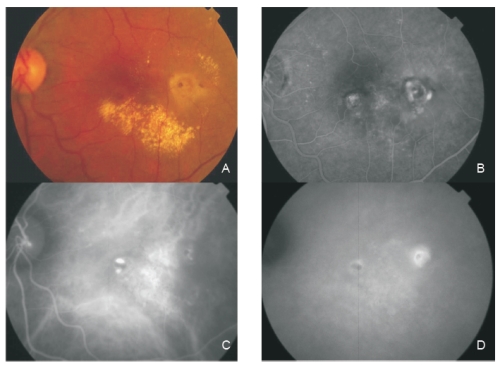

Figure 4 - Fundus colour photography (A) reveals the presence of circinate lipidic exudation surrounding a reddish-orange lesion temporal to the fovea. Late phase fluorescein angiography (B) shows a diffuse leakage with juxtafoveal involvement and two focal areas of staining and leakage. Two polypoidal foci separated by an abnormal choroidal vascular network are observed on ICG intermediate phase (C). Late phase ICG (D) shows an hiperfluorescent plaque, a more temporal hot spot (active polyp) and a more nasal hypofluorescent spot with hyperflluorescent borders (apparently inactive polyp).

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of PCV with central serous chorioretinopathy, AMD with choroidal neovasculazrization, inflammatory conditions and tumors is not always easy and needs ICG for a clear differentiation.

Retinal vascular lesions such as retinal artery macroaneurysms and retinal microaneurysms may be mistaken for polypoidal lesions based on ICG findings, but can be easily differentiated with good stereopairs made available during the ICGA.

Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy is a primary cause of macular serous retinal detachment without hemorrhage in patients over 50 years of age in Asian population(43).

Since clinical and fluorescein angiographic findings are often indistinguishable among central serous chorioretinopathy, PCV, and occult choroidal neovascularization, ICG might help to establish a more definitive diagnosis(22,44).

Central serous chorioretinopathy shows staining or late leakage but not an abnormal choroidal vascular network neither polyps.

Both these conditions are part of the pachychoroid spectrum of diseases characterised by loss of fundus tessellation, increased choroidal thickness, dilated large choroidal vessels in Hallers layer of the choroid, and attenuation of the choriocapillaris and Sattler’s layer.

The differential diagnosis becomes more challenging when lipid exudation and small PED are associated. ICG may be helpful differentiating PED from polypoidal lesions.

Small PED from central serous chorioretinopathy become hypofluorescent in late phases ICG and hyperfluorescent in late phases fluorescein angiography.

In contrast, polypoidal lesions are usually hyperfluorescent in late phases ICG because of its vascular nature(22).

PCV represents a subtype of type 1 CNV in AMD(11,15,23,24,25).However, some features distinguish PCV from other subtypes of CNV: eyes with PCV are characterized by a higher incidence of neurosensory detachments, greater neurosensory detachment height, and less intraretinal edema than eyes with occult or predominantly classic CNV(45).

Non polypoidal lesions in exudative AMD patients tend to produce small calibre vessels that are associated with grayish membranes not easily observed clinically, in contrast with the reddish-orange lesions clinically observed in PCV and corresponding to vascular saccular polypoid lesions(24,45,47).

Stromal choroidal fibrosis is common in predominantly classic and occult lesions but is quite rare in PCV.

PED associated with CNV in AMD has a poor prognosis whilst PED in PCV lesions virtually never forms fibrotic scars(22,24,39).

The natural evolution of CNV in AMD eyes to fibrosis and disciform scar is not observed in PCV eyes.

Tumoral lesions like choroidal circumscribed hemangioma, renal cell carcinoma or metastasis from carcinoid syndrome may also be confused with PCV(39). Again ICG is essential for differentiation.

Choroidal hemangiomas show, in general, a rapid filling of dye in very early phases and a washout in late phases.

ICG characteristic lesions of PCV are not observed in choroidal or metastatic tumors and ultrasound is also effectiveFigure 4. for characterization of the tumoral mass.

Inflammatory lesions, like posterior scleritis, multifocal choroiditis, panuveitis, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, Harada disease, sympathetic uveitis and birdshot chorioretinopathy may also be confused with PCV.

PCV is not associated with anterior or posterior uveitis neither with leakage nor staining of the optic disc in fluorescein angiography(4,22,24,39).

Lipid deposition, often observed in PCV is not commonly seen in inflammatory conditions.

Scleral or choroidal thickening and liquid in the subtenon space have never been described in PCV eyes(24,39).

Treatment

Treatment of PCV lesions is only recommended when central vision is being threatened by persistent and progressive exudative changes.

Otherwise, a conservative approach is recommended.

Different treatment modalities like laser photocoagulation, transpupillary thermotherapy, PDT and surgery or intravitreal antiangiogenic drugs have been reported.

To date, only one randomized, controlled clinical trial (RCT) has been published to prove the efficacy and safety of ranibizumab vs PDT or PDT plus ranibizumab (the EVEREST trial).

There are currently two ongoing major RCT which will provide more robust evidence supporting the most optimal therapy for the condition.

Direct laser photocoagulation of leaking polyps has proven short-term safety and efficacy for extrafoveal lesions(46-49).

Other authors, however, described poor results(50) and persistence or even increasing exudation in up to 44% of the cases(15), or VA decrease of 2 or more lines in near half of the eyes and legal blindness in up to two third of the eyes(35).

Yuzawa et al.(49) reported good efficacy of laser photocoagulation in near 90% of the eyes if all the polyps and abnormal vascular network were treated.

If the treatment involved only the polyps, more than half of the eyes suffered VA decrease related with exudation, recurrences or foveal scars. Direct laser photocoagulation of feeder vessels, identified in ICG, was also reported as showing VA improvement of 2 or more lines in 8 out of 15 eyes(51).

Considering the possibility of using other treatment modalities, laser photocoagulation should be reserved for well defined extrafoveal active polyps.

Transpupillary thermotherapy has shown to be useful in PCV(52).

A large number of reports on PDT in subfoveal PCV has been published((23,26,53-57).

Results at one year and even at two years are apparently superior to those of PDT in predominantly classic or occult CNV.

A longer follow-up shows a trend to a progressive but not significant VA decline at two(57) and 3 years follow-up(58):

The rate of eyes gaining a significant amount of vision dropped from 26% in the first year to 15% in the third year, and the rate of eyes with significant VA loss (3 or more ETDRS lines) increased from 17% to 26%.

A high rate of recurrence (44%) occurred during the 3-years follow-up but it was not associated with significant VA decline(58).

This high rate of recurrences may be associated with a poor response of the vascular network to PDT(59).

VA decline at 3 years may partially be explained by photoreceptors death due to chronic or recurrent neurosensory detachment, massive hemorrhages and progressive RPE atrophy.

The number of treatments decreases markedly after the first year from an average of 2.0 to 0.4 and 0.5 in the second and third years respectively(58).

Complications like subretinal haemorrhages, haemorrhagic PED or even massive hemorrhages have been associated to PDT in PCV eyes(60).

However, all of these complications may also occur without any treatment.

Surgical removal of polypoidal lesions and associated hemorrhages has been reported(15-19,61)

with and without macular translocation.

Considering the potential alternative treatments and the high rate of serious complications, macular translocation is no longer being considered for PCV(62).

The relatively large vascular lesions of PCV patients needs to be considered if a vitrectomy is planned in cases without associated massive hemorrhage.

Intravitreal antiangiogenic drugs, like bevacizumab(63) and ranibizumab(64) have been used for treating PCV eyes.

Ranibizumab short-term results(64) seem to be promising in terms of maintenance or improvement of VA and resolution of subretinal fluid and PED.

Polyps were reported to disappear in 69% of the cases at 3 months when using ranibizumab(64) but not with bevacizumab(63).

Intravitreal bevacizumab appeared also to result in stabilisation of vision and reduction of exudative retinal detachment in PCV patients in short-term evaluation.

However, it had limited effectiveness in causing regression of the polypoidal lesions(63).

Some exudative AMD eyes refractory to ranibizumab or bevacizumab may be, in fact, PCV cases.

Combined treatments associating PDT and intravitreal ranibizumab or bevacizumab have been reported to show good efficacy in these refractory cases of AMD(65).

The EVEREST study is the first multicenter, double-masked,ICG-guided randomized controlled trial with an angiographic treatment outcome designed to assess the effect of Visudyne® (PDT) alone or in combination with Lucentis® (ranibizumab) compared with Lucentis® alone in patients with symptomatic macular PCV.

A total of 61 PCV patients of Asian ethnicity from 5 countries (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, Thailand, and Singapore) participated in the study.

The six months EVEREST study results(66) suggests that in a majority of patients, Visudyne® therapy, with or without Lucentis®, may lead to complete regression of the polyps that can cause vision loss in patients with PCV.

A complete polyp regression (primary endpoint) was achieved in 77.8% of patients who received the Visudyne® – Lucentis® combination, in 71.4% of Visudyne® monotherapy patients and in 28.6% of patients in the Lucentis® monotherapy group (p=0.0018 for combination, p=0.0037 for Visudyne® vs Lucentis®).

Best corrected VA from baseline to month six improved in average in all groups with patients in the combination group achieving the highest gain (+10.9 letters from baseline). Lucentis® monotherapy patients gained +9.2 letters, and Visudyne® monotherapy patients +7.5 letters. Differences between the groups are not statistically significant.

All therapies were well tolerated and the safety findings were consistent with the established safety profiles of Visudyne® and Lucentis®.

Three multicentre randomized clincial trials are beeing runned with Ranibizumab (EVEREST II) and Aflibercept (PLANET AND ATLANTIC) comparing the efficacy of anti-VEGF alone or in combination with PDT.

The results will help to clarify if a combined treratment is necessary for polyps closure, resolution of exudation and visual acuity imporovement.

The EVEREST II is a phase 4, 2-year randomized clinical trial comparing ranibizumab alone with a combined teraphy of ranibizumab plus verteporfin PDT in 321 Asian patients.(71,41)

The PLANET randomized clinical trial enrolled 331 patients in Asia and in two European countries.

It is a phase 3-4, 1-year study comparing aflibercept alone with aflibercept plus verteporfin PDT in patients with PCV.(72)

The ATLANTIC study is a phase 4, 1-year randomized clinical trial, being runned in Portugal and Spain, comparing intravitreal treat and extend aflibercept monotherapy with aflibercept treat and extend regimen with adjunctive PDT in patients with PCV. (73)

Combined therapies

The adjunctive use of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide with PDT did not appear to result in additional benefit in the PDT treatment of PCV.

A retrospective analysis of PCV patients who underwent PDT with or without intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide, with a follow-up of 2 or more years, was reported in 27 eyes and showed to have a non-sustained effect after 1 year.(67)

The combination therapy between PDT and an anti-VEGF showed encouraging results including improved vision, reduced incidence of subretinal hemorrhage and reduced recurrence of polyps, when compared to PDT monotherapy for PCV. Reduced-fluence PDT combined with intravitreous bevacizumab for PCV improved vision and reduced complications.(68) even at two years.(69)

Combined treatment with PDT plus anti-VEGF should be considered in eyes diagnosed with leakage from the branching vascular network and the polyps, in eyes with visible exudation associated with PED and when ICGA results do not permit clearly to distinguish between PCV and CNV and when both conditions co-exist.(70)

The results of the three ongoing multicenter and randomized studies will certainly help to clarify the need to use or not combined therapies in the treatment of PCV.

Conclusion

PCV may be considered a subtype of exudative AMD.

ICG is always mandatory for the diagnosis of PCV, showing a unique lesion – an abnormal inner choroidal vascular network with polypoidal structures at the borders.

OCT and fundus findings may complement the diagnosis.

PCV needs to be differentiated from other forms of exudative AMD, central serous chorioretinopathy, inflammatory conditions and some choroidal tumors.Photodynamic therapy with Visudyne®, alone or in combination with antiangiogenic drugs, seems to be necessary for a complete resolution of the polypoidal lesions.

References - Neovascular Phenotypes: Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

References - Neovascular Phenotypes: Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

- Yannuzzi LA. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. The Macula Society Meeting. Miami, USA, February 5, 1982. 1982;1.

- Kleiner RC, Brucker AJ, Johnston RL. The posterior uveal bleeding syndrome. Retina 1990;10(1):9-17.

- Stern RM, Zakov ZN, Zegarra H, Gutman FA. Multiple recurrent serosanguineous retinal pigment epithelial detachments in black women. Am J Ophthalmol 1985;100(4):560-569.

- Cheung CM, Yang E, Lee WK, Lee GK, Mathur R, Cheng J, Wong D, Wong TY, Lai TY. The natural history of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: a multi-center series of untreated Asian patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015;253(12):2075-85.

- Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB, Goldbaum M, Scassellati-Sforzolini B, Guyer DR, Spaide RF, Maberley D, Wong DW, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Fisher YL, Orlock DA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy masquerading as central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 2000;107:767–777.

- Li H, Wen F, Wu D. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in a patient with circumscribed choroidal hemangioma. Retina 2004;24:629–631.

- Bartlett HM, Willoughby B, Mandava N. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in a patient with melanocytoma of the optic nerve. Retina 2001;21:396–399.

- Mauget-Faÿsse M, Cornut PL, Quaranta El-Maftouhi M, Leys A. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in tilted disk syndrome and high myopia with staphyloma. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:970–975.

- Fine HF, Ferrara DC, Ho IV, Takahashi B, Yannuzzi LA. Bilateral choroidal osteomas with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2008;2:15–17.

- Samira K, Engelbert ME, Yutaka I, Freund KB. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: Simultaneous Indocyanine Green Angiography and Eye-Tracked Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Findings. Retina 2012;32:1057-1068.

- Ciardella AP, Donsoff IM, Huang SJ, Costa DL, Yannuzzi LA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49(1):25-37.

- Scassellati-Sforzolini B, Mariotti C, Bryan R, Yannuzzi LA, Giuliani M, Giovannini A. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Italy. Retina 2001;21(2):121-125.

- Yuzawa M, Mori R, Kawamura A. The origins of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89(5):602-607.

- MacCumber MW, Dastgheib K, Bressler NM, Chan CC, Harris M, Fine S, Green WR. Clinicopathologic correlation of the multiple recurrent serosanguineous retinal pigment epithelial detachments syndrome. Retina 1994;14(2):143-152.

- Lafaut BA, Leys AM, Snyers B, Rasquin F, De Laey JJ. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Caucasians. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000;238:752–9.

- Rosa RH Jr, Davis JL, Eifrig CW. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: clinicopathologic correlation of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(4):502-508.

- Okubo A, Sameshima M, Uemura A, Kanda S, Ohba N. Clinicopathological correlation of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy revealed by ultrastructural study. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86 (10):1093-1098.

- Terasaki H, Miyake Y, Suzuki T, Nakamura M, Nagasaka T. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy treated with macular translocation: clinical pathological correlation. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86(3):321-327.

- Nakashizuka H, Mitsumata M, Okisaka S, Shimada H, Kawamura A, Mori R, Yuzawa M. Clinicopathologic findings in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49(11):4729-4737.

- Okubo A, Hirakawa M, Ito M, Sameshima M, Sakamoto T. Clinical features of early and late stage polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy characterized by lesion size and disease duration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;246(4):491-499.

- Guyomarch J, Jean-Charles A, Acis D, Donnio A, Richer R, Merle H. Vasculopathie polypoidale choroidienne idiopathique: aspects cliniques et angiographiques. J Fr Ophtalmol 2008;31(6 Pt 1):579-584.

- Spaide RF, Yannuzzi LA, Slakter JS, Sorenson J, Orlach DA. Indocyanine green videoangiography of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 1995;15(2):100-110.

- Silva RM, Figueira J, Cachulo ML, Duarte L, Faria JR., Cunha-Vaz JG. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005;243(10):973-979.

- Yannuzzi LA, Wong DW, Sforzolini BS, Goldbaum M, Tang KC, Spaide RF, Freund KB, Slakter JS, Guyer DR, Sorenson JA, Fisher Y, Maberley D, Orlock DA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascularized age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117(11):1503-1510.

- Yannuzzi LA, Ciardella A, Spaide RF, Rabb M, Freund KB, Orlock DA. The expanding clinical spectrum of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115(4):478-485.

- Ahuja RM, Stanga PE, Vingerling JR, Reck AC, Bird AC. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in exudative and haemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachments. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84(5):479-484.

- Cheng Y, Huang L, Li X, Zhou P, Zeng W, Zhang C. Genetic and functional dissection of ARMS2 in age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. PLoS One 2013;8: e53665.

- Kondo N, Honda S, Kuno S, Negi A. Coding variant I62V in the complement factor H gene is strongly associated with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Ophthalmology 2009;116(2):304-310.

- Gotoh N, Nakanishi H, Hayashi H, Yamada R, Otani A, Tsujikawa A, Yamashiro K, Tamura H, Saito M, Saito K, Iida T, Matsuda F, Yoshimura N. ARMS2 (LOC387715) variants in Japanese patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;147(6):1037-1041.

- Zhang X, Wen F, Zuo C, Li M, Chen H, Wu K. Association of genetic variation on chromosome 9p21 with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;52:8063-8067.

- Gotoh N, Yamada R, Nakanishi H, Saito M, Iida T, Matsuda F, Yoshimura N. Correlation between CFH Y402H and HTRA1 rs11200638 genotype to typical exudative age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy phenotype in the Japanese population. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2008; 36(5):437-442.

- Kondo N, Honda S, Ishibashi K, Tsukahara Y, Negi A. Elastin gene polymorphisms in neovascular age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49(3):1101-1105.

- Chen H, Liu K, Chen LJ, Hou P, Chen W, Pang CP. Genetic associations in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Vis 2012;18:816-829.

- Ross RD, Gitter KA, Cohen G, Schomaker KS. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy associated with retinal arterial macroaneurysm and hypertensive retinopathy. Retina 1996;16(2):105-111.

- Wen F, Chen C, Wu D, Li H. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in elderly Chinese patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004;242(8):625-629.

- Uyama M, Wada M, Nagai Y, Matsubara T, Matsunaga H, Fukushima I, Takahashi K, Matsumura M. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: natural history. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133 (5):639-648.

- Yang SS, Fu AD, McDonald HR, Johnson RN, Ai E, Jumper JM. Massive spontaneous choroidal hemorrhage. Retina 2003;23(2):139-144.

- Kwok AK, Lai TY, Chan CW, Neoh EL, Lam DS. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Chinese patients. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86(8):892-897.

- Klais CM, Ciardella A, Yannuzzi LA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. In: Virgil Alfaro D, Liggett PE, Mieler WF, Quiroz-Mercado H, Jager RD, Tano Y, eds. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia, USA. Lippincott-Raven. 2006;6:53-63.

- Ojima Y, Hangai M, Sakamoto A, Tsujikawa A, Otani A, Tamura H, Yoshimura N. Improved visualization of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy lesions using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Retina 2009;29(1):52-59.

- Kameda T, Tsujikawa A, Otani A, Sasahara M, Gotoh N, Tamura H, Yoshimura N. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy examined with en face optical coherence tomography. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2007;35(7):596-601.

- Wang M, Zhou Y, Gao SS, Liu W, Huang Y, Huang D, Jia Y. Evaluating Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy With Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016 Jul 1;57(9):OCT526-32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18955.

- Hikichi T, Ohtsuka H, Higuchi M, Matsushita T, Ariga H, Kosaka S, Matsushita R. Causes of macular serous retinal detachments in Japanese patients 40 years and older. Retina 2009;29(3):395-404.

- Yannuzzi LA, Sorenson J, Spaide RF, Lipson B. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV). Retina 1990;10(1):1-8.

- Ozawa S, Ishikawa K, Ito Y, Nishihara H, Yamakoshi T, Hatta Y, Terasaki H. Differences in macular morphology between polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and exudative age-related macular degeneration detected by optical coherence tomography. Retina 2009;29(6):793-802.

- Moorthy RS, Lyon AT, Rabb MF, Spaide RF, Yannuzzi LA, Jampol LM. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy of the macula. Ophthalmology 1998;105(8):1380-1385.

- Guyer DR, Yannuzzi LA, Ladas I, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Orlock D. Indocyanine green-guided laser photocoagulation of focal spots at the edge of plaques of choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114(6):693-697.

- Gomez-Ulla F, Gonzalez F, Torreiro MG. Diode laser photocoagulation in idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 1998;18(5):481-483.

- Yuzawa M, Mori R, Haruyama M. A study of laser photocoagulation for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2003;47(4):379-384.

- Yamanishi A, Kawamura A, Yuzawa M. Laser photocoagulation for idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Jpn J Clin O 1998;52:1691-1694.

- Nishijima K, Takahashi M, Akita J, Katsuta H, Tanemura M, Aikawa H, Mandai M, Takagi H, Kiryu J, Honda Y. Laser photocoagulation of indocyanine green angiographically identified feeder vessels to idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137(4):770-773.

- Mitamura Y, Kubota-Taniai M, Okada K, Kitahashi M, Baba T, Mizunoya S, Yamamoto S. Comparison of photodynamic therapy to transpupillary thermotherapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Eye (Lond) 2009;23(1):67-72.

- Gomi F, Ohji M, Sayanagi K, Sawa M, Sakaguchi H, Oshima Y, Ikuno Y, Tano Y. One-year outcomes of photodynamic therapy in age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Japanese patients. Ophthalmology 2008;115(1):141-146.

- Mauget-Faysse M, Quaranta-El MM, De La ME, Leys A. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in the treatment of exudative idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2006;16(5):695-704.

- Chan WM, Lam DS, Lai TY, Liu DT, Li KK, Yao Y, Wong TH. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for symptomatic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: one-year results of a prospective case series. Ophthalmology 2004;111(8):1576-1584.

- Sayanagi K, Gomi F, Sawa M, Ohji M, Tano Y. Long-term follow-up of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245(10):1569-1571.

- Tsuchiya D, Yamamoto T, Kawasaki R, Yamashita H. Two-year visual outcomes after photodynamic therapy in age-related macular degeneration patients with or without polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy lesions. Retina 2009;29(7):960-965.

- Silva Leal S, Silva Rufino, Figueira J, Cachulo ML, Pires I, Faria de Abreu JR, Cunha-Vaz JG. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: Results after 3 years of follow-up. Retina 2010;30(8):1197-205.

- Lee WK, Lee PY, Lee SK. Photodynamic therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: vaso-occlusive effect on the branching vascular network and origin of recurrence. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2008;52(2):108-115.

- Sayanagi K, Gomi F, Sawa M, Ohji M, Tano Y. Long-term follow-up of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245(10):1569-1571.

- Shiraga F, Matsuo T, Yokoe S, Takasu I, Okanouchi T, Ohtsuki H, Grossniklaus HE. Surgical treatment of submacular hemorrhage associated with idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;128(2):147-154.

- Fujii GY, Pieramici DJ, Humayun MS, Schachat AP, Reynolds SM, Melia M, De Juan E Jr. Complications associated with limited macular translocation. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130(6):751-762.

- Lai TY, Chan WM, Liu DT, Luk FO, Lam DS. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) with or without photodynamic therapy for the treatment of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92(5):661-666.

- Reche-Frutos J, Calvo-Gonzalez C, Donate-Lopez J, Garcia-Feijoo J, Leila M, Garcia-Sanchez J. Short-term anatomic effect of ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2008;18(4):645-648.

- Reche-Frutos J, Calvo-Gonzalez C, Donate-Lopez J, Garcia-Feijoo J, Leila M, Garcia-Sanchez J. Short-term anatomic effect of ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2008;18(4):645-648.

- QLT INC: 6-month results from EVEREST study evaluating Visudyne(R) therapy in patients with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Available at: http://www.4-traders.com/QLT-INC-10600/news/QLT-INC-6-month-results-from-EVEREST-study-evaluating-Visudyne-R-therapy-in-patients-with-polypoi-13292269/. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Lai TY, Lam CP, Luk FO, Chan RP, Chan WM, Liu DT, Lam DS. Photodynamic therapy with or without intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for symptomatic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2010;26:91-95.

- Ricci F, Calabrese A, Regine F, Missiroli F, Ciardella AP. Combined reduced fluence photodynamic therapy and intravitreal ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 2012;32:1280-1288.

- Yoshida Y, Kohno T, Yamamoto M, Yoneda T, Iwami H, Shiraki K. Two-year results of reduced-fluence photodynamic therapy combined with intravitreal ranibizumab for typical agerelated macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Jpn J Ophthamol 2013;57:283-293.

- Koh AH; Expert PCV Panel, Chen LJ, Chen SJ, Chen Y, Giridhar A, Iida T, Kim H, Yuk Yau Lai T, Lee WK, Li X, Han Lim T, Ruamviboonsuk P, Sharma T, Tang S, Yuzawa M. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment. Retina 2013;33:686-716.

- Visual Outcome in Patients With Symptomatic Macular PCV Treated With Either Ranibizumab as Monotherapy or Combined With Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy. (EVEREST II). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01846273

- Aflibercept in Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy (PLANET) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02120950)

- Marques JP, Farinha C, Costa MA, Ferrão A, Sandrina Nunes, Rufino Silva. Protocol for a randomised, double-masked, sham-controlled phase 4 study on the efficacy, safety and tolerability of intravitreal aflibercept monotherapy compared with aflibercept with adjunctive photodynamic therapy in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: the ATLANTIC study. BMJ Open 2017 August 28, 7 (8): e015785